Oregon legislators are pursuing a proposal to become the second state in the country to mandate climate change education for K-12 public school students, a move that is likely to intensify the ongoing culture wars surrounding education in the United States.

Numerous high school students in Oregon have expressed their support for the bill, asserting that they care deeply about the issue of climate change. Some educators and parents contend that teaching about climate change could equip the next generation with the tools to confront this challenge more effectively. However, others believe schools should prioritize reading, writing, and math education, particularly after the pandemic led to plummeting test scores.

The news today in the world is raising global warming awareness. Schools are the primary areas, to begin. Schools in the United States have become embroiled in a politically fraught conflict over the curriculum and how topics such as gender, sex education, and race should be approached, or even if they should be taught at all.

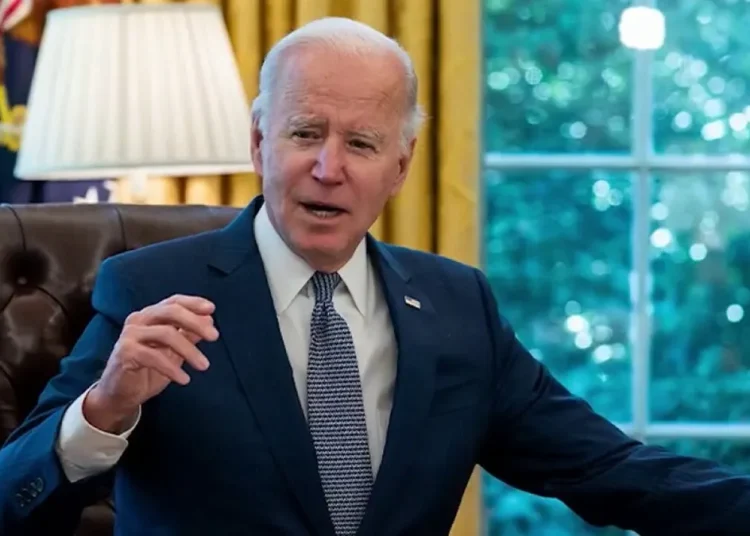

Democratic Senator James Manning’s opinion:

According to Democratic Senator James Manning, one of the primary proponents of the bill, even elementary school children have emphasized to him the significance of climate change. “We’re referring to third and fourth graders who possess the foresight to comprehend how rapidly our world is changing,” he stated during a hearing at the state Capitol in Salem on Thursday.

Connecticut is the only state in the US that currently has a law mandating instruction on climate change. It is potentially the first time such legislation is introduced in Oregon, according to researchers for the legislature. Similar bills are under consideration by lawmakers in California and New York.

Under Senator Manning’s proposal, every school district in Oregon would be required to create a climate change curriculum within three years that covers ecological, societal, cultural, political, and mental health aspects of climate change.

There is no clarity on how Oregon would enforce the law mandating climate change instruction. Senator Manning indicated that he plans to remove an unpopular proposal that would impose financial penalties on districts that fail to comply, but there is no clarity on introducing a new plan.

The bill does not specify the number of hours of instruction required for the state’s education department to approve a district’s climate change curriculum at this time.

Many states have established learning standards that state education boards largely determine. It covers the topic of climate change, although the degree of coverage differs from state to state. The Next Generation Science Standards, which require middle school students to study climate science and high school students to learn how human activity impacts the climate, have been adopted by twenty states and Washington, D.C.

Different viewpoints of school teachers

Gabriel Burke, a high school sophomore, testified in favor of the bill, expressing concern about the environment’s future. He said, “In 100 years, will we have to teach our children what trees are because they don’t exist anymore? The thought horrifies me. For the sake of our survival, my generation must begin learning about climate change at a young age.

Kyler Pace, a grade school teacher in Sherwood, Oregon, testified against the bill, saying that teachers are already struggling to address pandemic learning losses, and adding climate change lessons on top of reading, writing, math, science, and social studies would be a “heavy lift” that would burden teachers.

At Toll Gate Grammar School, Suzanne Horsley, a wellness teacher, strives to provide age-appropriate climate change lessons. In her physical education classes for students in grades K-2, she conducts a game using pretend trees and bean bags representing carbon. The game aims to teach students that tree reduction leads to higher levels of atmospheric carbon.

In Suzanne Horsley’s lesson plan for teenagers, they are taught about the disproportionate impact of climate change on low-income communities. They also study air quality maps in areas with high industrial activity or car traffic.

Conclusion:

According to surveys by Columbia University’s Teachers College and the Yale Program on Climate Communication, Americans with this news today in the world believe that climate change and global warming should be taught in schools. However, some people still view climate change as a politically controversial topic.